Despite growing up in Brentwood, I knew little of St. Charles, just as I knew little of Leverton - two institutions for young offenders hidden within the town's green perimeter. Unlike asylums, neither was particularly visible: St. Charles a low-rise complex screened by trees; Leverton a historic manor house nestled between stables and the M25. The charitable interpretation of their location is that it would aid rehabilitation, though Essex has long been handed the unwanted or unassimilable aspects of London - be it abundant landfills (the prevailing easterly breeze keeping the stench away from the city), the factories and car plants that pollute and despoil vast areas, or the large housing estates for those displaced by slum clearance (such as the East Ham estate on which I grew up).

St. Charles opened in 1971, one of only two Youth Treatment Centres in the entire country, the other being Glenthorne in Birmingham. Dubbed "the Children's Broadmoor", it housed children from the age of ten to eighteen who were guilty of the most serious criminal offences or who were too violent or disturbed to be treated elsewhere. Although approved by the previous Labour government, the centre became, in the 70s and 80s, a key component of the Conservative policy of "cracking down" on youth crime, with the number of juveniles imprisoned in the UK increasing by 500% between 1965 and 1980.

In the twenty-four years it was open, St Charles housed and treated some of the most vulnerable and damaged in society, yet even locally it was little-known or ignored. Childhood criminality and dysfunction are both problems from which people have always sought to avert their eyes, lest they be confronted by their own complicity and guilt - and the institutes's life post-closure has followed a similar pattern. There remains little interest in the site, and certainly no mention of its fraught history. Commentary in the local press has been limited merely to the redevelopment of the site into luxury housing - and a brief but ferocious protest in 2001 against proposals for a new secure unit on the site.

I had almost forgotten about the site too, stumbling across it by accident when seeking a different way to approach a nearby park. At first, I'd assumed it was some kind of industrial area, but as soon as I saw the full extent of the security measures in place, I immediately realised where I was. Inexplicably, a vast steel gate had been left slightly ajar; and in the absence of any apparent patrols or surveillance, I decided to explore.

The houses were perhaps the most interesting aspect of the site, though there remained few traces of former inmates. In one room I stumbled across some cards and decorations, in another some paperwork and clothes – but very little else. The majority have been cleared thoroughly, with most of the rooms containing nothing but light bulbs and curtains.

The entire complex was circumscribed by an immense metallic fence; and viewed from the perimeter the sense was of genuine dread (visiting in the depth of winter only heightening the unease). Once the fence had been negotiated, however, the reality was far more mundane, if no less bleak. The centre essentially amounted to a series of houses, around which were scattered various amenities such as classrooms, workshops and gymnasia. Remarkably, given it’s been derelict for ten years, all the windows were intact, and there were almost no instances of graffiti. (Upon entering a room, the only footprints I saw were those of foxes and badgers).

In terms of layout, the ground floor of each house was given over to several communal areas, while bedrooms and cells dominated the upper storeys. In each house, there were also some rooms for violent inmates - the doors to which were at least twenty centimetres thick. In each and every room, there were also bars across the windows, a dismal view rendered even more pinched and claustrophobic.

Elsewhere, there were workshops (woodwork projects still lay unfinished on benches), and perhaps most impressively of all, a gymnasium and basketball court. It was only really in these areas of the prison that it was possible to forget where you were. There were even moments when it felt just like a school or leisure centre. It was only when you looked more closely – at the spiked gables or grated skylights – that you realised escape would be almost impossible.

I found the entire complex genuinely unsettling, despite (or perhaps because of) the numerous concessions to the domestic. Organised into a serious of houses (or families), St. Charles differed in many respects to the borstals and young offenders' institutes of the 70s and 80s - the complexity of many residents' problems encouraging more intensive care and supervision. The result was a kind of halfway-house between a children's home and prison - the atmosphere familiar yet also disorienting, at each turn symbols of both comfort and control.

While some - particularly those with chaotic or dangerous backgrounds - may have welcomed these constraints, others must surely have bristled at this strange simulacrum of home. (So much depending too, of course, on the particular character of the adults and children assigned to each house).

I visited St. Charles for a second time a few months later, but little had changed. A few more broken windows, an accretion of dead birds on the upper floors - but nothing of any significance. Its singular atmosphere remained; cobalt skies and the autumn sun doing little to offset its bleakness. Even in those rooms facing the sun, the sense of confinement was pronounced. Outside, the sense of restriction eased only slightly, despite the abundance of trees and various flora; the enormous fence looming large on the horizon whichever way you turned.

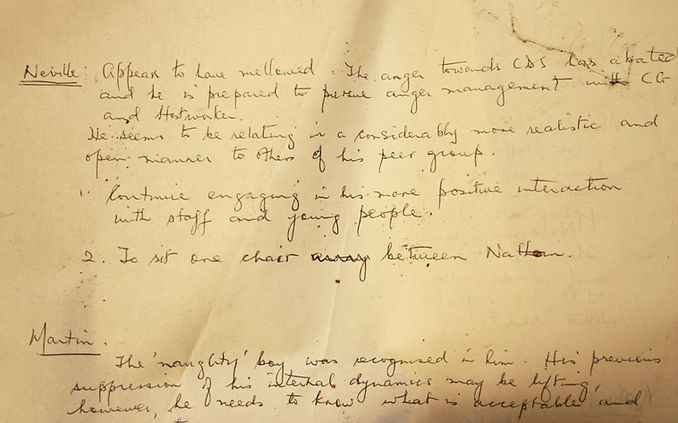

Towards the end of my visit that I finally unearthed some paperwork – a small timetable and some notes from a treatment group. The timetable was reasonably straightforward – detailing classes such as Geography, Computing and Horticulture - but the notes were of far more interest. Written by one of the staff, they offered a brief analysis of five of the Centre’s inmates.

Of Neville, a staff member wrote the following: "Continues to split the staff group, especially around going home. Also continues to live in a fantasy world. Appears to be presenting well in the Skills Centre, but on his return to the house, he poisons everyone.” ...This person later adds: “can have a gold tooth if parents prepared to pay for it”. Martin, meanwhile, needed training on "normal social mannerisms" and " to know what is acceptable and appropriate."- though was bizarrely granted permission to buy a cigar. There was, at least, some sign of rehabilitation amongst the violence and disturbance - with Neville reported "to have mellowed" and be "prepared to pursue anger management," while Mark had an interview in Scarborough with a mechanics that sounded promising.

In terms of treatment, the courses most readily prescribed were counselling, social skills training and anger management, though the notes testify to the difficulties in delivering each session, with disruption and suppression frequent. It's impossible, of course, to measure individual impacts given the limited nature of the notes - but it was clear, nonetheless, how determined many staff were to prepare children for their release (and how concertedly many children resisted such intervention and control). Given the extreme behaviour of many inmates, the ratio of staff to children was a remarkable 3:1 - and the power imbalance this represented, however well-intentioned, must have been pronounced.

And yet despite the many failures of such institutions, it is important to remember that most staff were highly-trained and deeply committed to helping those in their care. Although inspections identified several instances of malpractice, the problems at St. Charles were as much those of conception and design - and of a society that fails to offer support until far too late.

As expected, the outside world appears only sparingly in the reports. R_____ was granted permission to visit his parents in hospital, A_____ to spend time with his birth mother – but the focus was overwhelmingly on institutional life. Similarly, there is very little sense of the inmate’s thoughts or experiences. As in most institutions, it is the voices of staff that predominate – the views of inmates found only in graffiti and minor acts of vandalism.

The criminal lawyer Chris Daw QC has described institutions like St Charles as "not just 'universities of crime', but a form of medieval survivalism, played out in gyms, corridors, dining halls...", adding that all evidence shows that "criminalising children causes more crime and therefore more victims – and locking children up even more so.." With limited space for genuine rehabilitation, or the welfare-based approaches that have been proven to work, such places become "places of misery and violence, often more dangerous than adult prisons." The unfortunate truth is that most of these children should have been helped years earlier, and their incarceration and treatment compounded this earlier neglect by significantly increasing the likelihood of reoffending.

An inspection by Social Services in 1988 was highly critical of the Centre, though few of the report's recommendations were implemented by the time the unit was again the subject of a major scandal. In January 1991, six months after being transferred to Glenthorne, a sixteen-year-old girl filed a complaint about her earlier treatment at St Charles. In her time at the unit, she was regularly injected with sedatives (frequently by force and without consent), held in solitary confinement for up to seven weeks at a time, restricted from almost all contact with the outside world, and even excluded from reviews of her case.

An investigation swiftly commissioned by Ministry of Health, found that several other children at St. Charles were similarly mistreated, and a complete restructuring of the centre's management was ordered - with the director, deputy director and several others suspended before eventually being fired.

The case received national coverage, though the success of the subsequent reorganisation was limited, despite the secondment of several staff members from Glenthorne. After struggling on for four more years, the centre finally closed in 1995; the Health Minister, John Bowis, declaring that there had been "problems of management and control which have proved difficult to resolve". At the time of its closure, it was operating far below its intended capacity of seventy - eventually catering to a mere six children - its poor reputation and increased provision elsewhere rendering the centre unviable.

The history and experiences of inmates must often have been traumatic; and yet all I was able to sense was absence - the population an undifferentiated mass. Viewed simply as places - derelict, forgotten, silent - these buildings are extraordinary; but with no human traces to cleave to, the desolation eventually becomes too much. (I remember feeling much the same at Cane Hill; my first visit all-encompassing, my last spent entirely in occupational therapy, knee-deep in patient artwork). Indeed, St Charles serves as a fascinating counterpoint to psychiatric hospitals. With asylums, there are always concessions to the outside world, be it geographical prominence, the abundance of windows - but here separation is absolute. A ten-metre metallic fence and the pervasiveness of razor wire utterly reject the idea of assimilation or contact. The cord with the outside world is cut completely.